When the newsrooms of the 70s changed from heavy Olivetti typewriters to whirring electric golf ball varieties, I was overjoyed and my fingers flew to greet the change. When the first Atex computer systems arrived I thought it could not get better and actually switched jobs in pursuit of the black screens with flickering green words. No pictures mind. And so the 21st Century is sheer heaven.

But how do you stay on top of it all. And as a journalist with less and less time to gather information how do you know what is reliable on the net. There are some great tools out there in the digital universe and from time to time we will help you locate it. Recently the Africa News Innovation Challenge (ANIC) and Media Monitoring Africa (MMA) joined forces to launch a site that helps you know who is most guilty of Churnalism, regurgitating content instead of telling us the news. The site is also tracking who is responsible for making unethical changes to online content without informing the public about stories that have been updated.

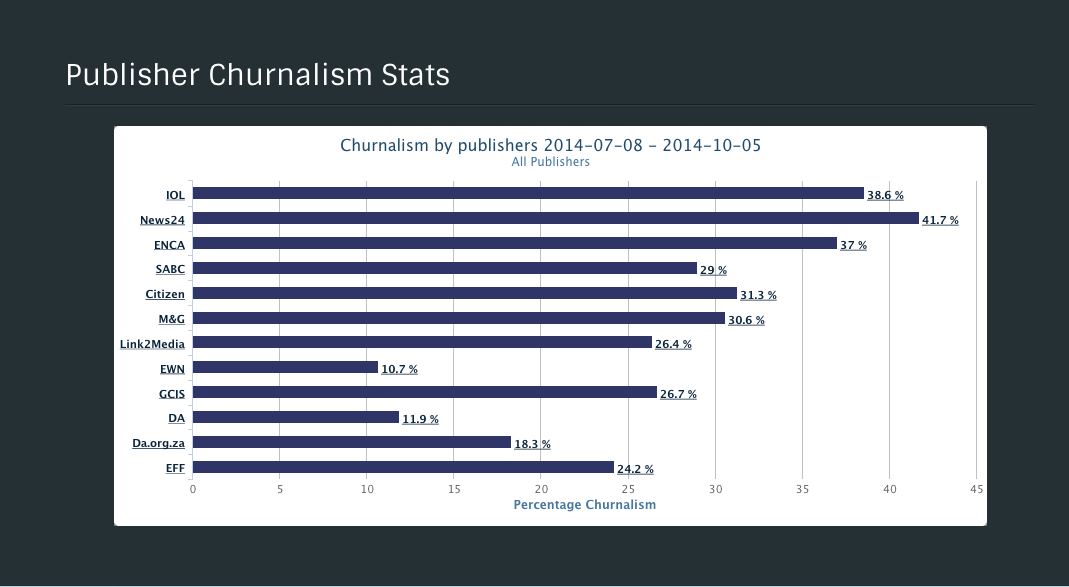

Graph of guilty journalists

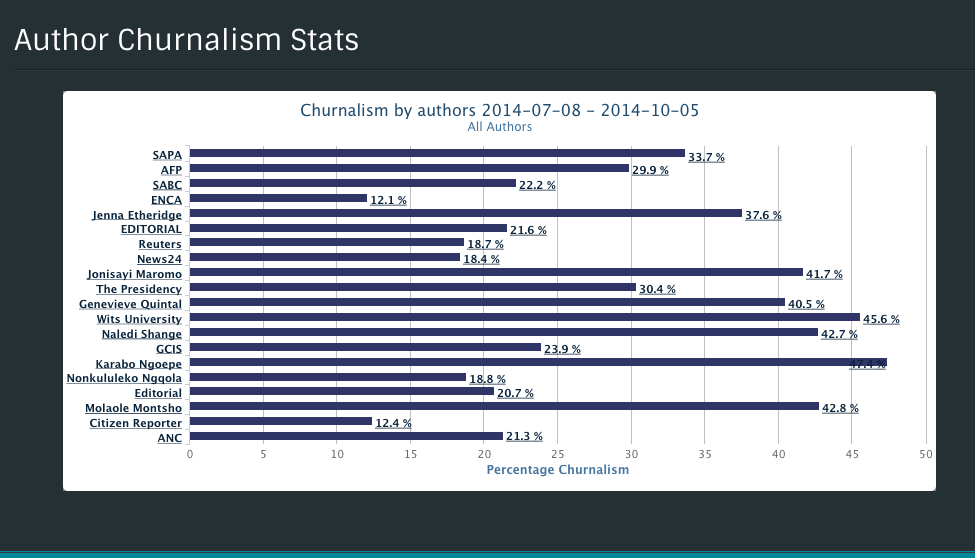

Not only does www.newstools.co.za list the companies most guilty of Churnalism but they also finger individual journalists.

“Who are the biggest regurgitators? Which media houses produce copy instead of the news?

We wanted to know not just if Churnalism occurs, but where, and how often and by who. The charts that follow show: the degree of churn across major media houses, then churn over time and finally a look at the biggest sources of Churnalism,” states the site.

Graph of guilty journalists

The same site has a service called NewsDiffs.

“NewsDiffs South Africa is there to track changes to news content over time. With paper based systems any changes to articles had to be reprinted. These days the media have the ability to change stories almost instantly, it is critical that when they do they let their readers know what changes have been made. Any editorial on a news story that undergoes changes should be clearly marked as updated,” they say.

Their first candidate for tracking change is the Mail & Guardian.

Mapping Digital Media

Somewhere in the back of our minds is the fact that television and radio across Africa is due to switch over from broadcasting analog signals to the new digital world by next year. The ambitious Open Society Foundation’s Mapping Digital Media project examines the impact of the “digital switchover” on journalism, democracy, and freedom of expression in 56 countries.

The process is complex but we don’t have to understand the technology to know that it will make a difference to all our lives. Of course it will free up the airwaves for a greater profusion Of Radio and TV stations but it’s not all good news, says the Open Society Foundation:

“Along with opportunities for more and better services, digitization can also have negative effects. Less-commercial producers may be forced to close, smaller languages may disappear from mainstream broadcasting, news and current affairs programming may be cut back, and powerful media businesses can become even more powerful—all with severe consequences for journalism, media pluralism, and democracy.

“The Mapping Digital Media project is the most extensive investigation of today’s media landscapes… The project includes analysis, and research from around the world on how digitization is changing media output, media freedom, and citizens’ access to quality news and information.”

The Mapping Digital Media report (available here) reveals common themes across the world:

- Governments and politicians have too much influence over who owns, operates, and regulates the media.

- Many media markets are rife with monopolistic, corrupt, or untransparent practices.

- It’s not clear where many governments and other bodies get their evidence for changes or updates to laws and policies on media and communication.

- Media and journalism online offer hope of new, independent sources of information, but are also a new battleground for censorship and surveillance.

- Data about the media worldwide are still uneven, unstandardized, and unreliable, and are often proprietary rather than freely accessible.