Zubeida Jaffer and Sibusiso Tshabalala

Sol Plaatje cannot give us all the answers, but his works teach us two indispensable lessons. First, to be a humanitarian it is not necessary to efface and extinguish one’s own cultural identity and heritage. Second in honouring one’s own language and history it is entirely unnecessary to dishonour the language and history of anyone else.

Kader Asmal

– Foreword to Plaatje’s Native Life In South Africa

Solomon Tshekiso Plaatje was a journalist extraordinaire. He was by all accounts the pioneer of pioneers. We take him as “exemplar and standard”, said former Education Minister Professor Kader Asmal in the foreword to Native Life in South Africa, the 1916 Plaatje classic republished in 2007.

“It reminds us that this country needs more Sol Plaatjes, more crusading journalists who use language like a rapier, not a sledgehammer, who know their stuff and argue their case on the basis of justice, reason and the facts,” said Asmal.

Plaatje, a largely self-taught man, could speak seven languages fluently. He translated William Shakespeare’s works into Setswana and collected African folklore and proverbs. He was a pioneer of journalism in our indigenous languages but wrote extensively in English as well. He defended tirelessly the rights of African people.

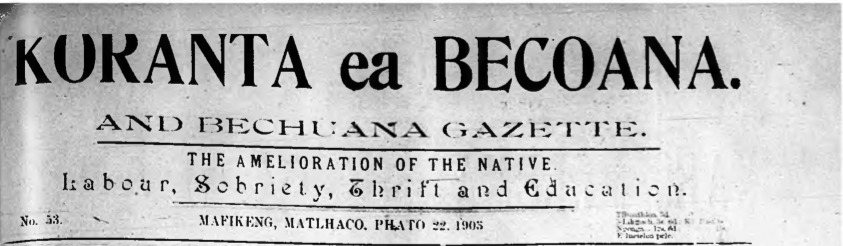

Screenshot of Koranta ea Becoana’s masthead. Online digitized edition courtesy of Wits University’s Historical Papers Research Archive.

On the Warpath With A Pen

Plaatje was born in the Boshof District of the Orange Free State in 1876. His parents– Johannes and Martha Plaatje –were Christians who worked for the missionaries. When he was born, they named him Thekiso, a Tswana name meaning that which you do for advantage or gain. His parents were signaling that he needed to seek advantage for himself and his people and so he did.

In his lifetime, Plaatje moved seamlessly from interviewing homeless people by the roadside to a meeting with the British Prime Minister. He gave talks and showed films at local schools and community centres. He once shared a podium with Marcus Garvey, the famous Jamaican ideologue who propagated the unification and empowerment of all Africans even those in the Diaspora.

As editor of the black-owned newspapers, Koranta ea Becoana (1901–1908) and Tsala ea Batho (1910–1915), Plaatje highlighted issues of great concern to Africans such as racism, injustice and exploitation.

When the Land Act of 1913 was passed, he used his pen to go on the warpath. He travelled around the country on a bicycle to research the effects of the new legislation. His work was published in 1916 as the famous classic, “Native Life in South Africa.” He meticulously reported on conditions around the country leaving us with first-hand accounts of the early years of dispossession.

The opening words of the first chapter of this book, have become immortalised:

“Awaking on Friday morning, June 20, 1913, the South African native found himself, not actually a slave, but a pariah in the land of his birth.”

Later he wrote:

“For to crown all our calamities, South Africa has by law ceased to be the home of any of her native children whose skins are dyed with a hue that does not conform to the regulation hue. “

Plaatje’s pen raised his national profile. He became the first Secretary-General and founding member of the South African Native National Congress (SANNC) in 1912.

Screenshot of Koranta ea Becoana’s masthead. Online digitized edition courtesy of Wits University’s Historical Papers Research Archive.

Rise of Protest Journalism

Reading the digitised editions of Koranta gives you a powerful glimpse into the world of Sol T Plaatje. At first glance, the masthead of Koranta ea Becoana seems like information for a tasteless self-help book. Beneath the name it states: The Amelioration of the Native – Labour, Sobriety, Thrift and Education.

But as you scroll down, you encounter the richness and contradictions. On the first pages colonial merchants vied with each other. Some sold bicycles, some medicine – like Hoffe’s remedy. If we can believe the advert, this remedy cured and prevented fever and was never known to fail. In true merchant bravura, some colonials offered their “selling skills”.

A story about the influential Barolong people who were seeking compensation from Imperial Britain in 1903, went to the heart of the issues of the day. Colonel Baden-Powell enlisted the Rolong to fight alongside the British in the Anglo-Boer War. Baden-Powell promised that compensation would follow, but this did not happen. To this day, the Rolong haven’t been compensated or even acknowledged.

Koranta, like other newspapers of that time, was modest in size and moderate in tone, with low circulation rates among a population with limited literacy. Yet they confronted a social system that discriminated against all.

Originally established by the editor of the Mafikeng Mail, G.H. Whales, Koranta began as a one-page newsletter supplement in Tswana with an initial circulation of 500. Silas Molema, of the prominent Barolong people, bought the paper from Whales to make way for Plaatje as Editor.

When Plaatje became Editor he increased it to two pages, appointed newsagents and solicited advertisements. By the end of 1902, Koranta was an 8-page title with a circulation of 2 000 nationwide. By the following year Molema and Plaatje set up a printing plant and built an office in Mafikeng. But his success with the paper was more than just operational. Koranta and subsequently Tsala ea Becoana were politically influential.

In several issues of the paper, he began his editorials with a Biblical quotation. This one comes from the Old Testament’s Song of Solomon.

“I am black, but comely, O ye daughters of Jerusalem, as the tents of Kedar. Look not upon me because I am black, because the sun hath looked upon me”.

This, like many of Plaatje’s writings indicated his strong Africanist commitment. By quoting Solomon – seemingly tongue in cheek – he hinted at the importance of a strong African identity in a world where racial discrimination was rife.

Screenshot of Koranta ea Becoana’s masthead. Online digitized edition courtesy of Wits University’s Historical Papers Research Archive.

Koranta was critical of the British administration in the Transvaal and Orange River Colonies. Here, Africans continued to suffer at the hands of violent police and a judicial system that did not protect their human rights. Plaatje expanded the newspaper’s protest agenda gradually. He campaigned for the better treatment of Africans employed in urban areas and contended that the African franchise and civil rights of the Cape Colony should be extended to the rest of the country.

The Gods Must Be Cruel

Plaatje was a complex man. Although prefacing his editorials with Biblical quotes, at times he railed against what he saw as the Divine order of things:

“The gods are cruel, and one of their cruelest acts of omission was that of giving us no hint that in very much less than a quarter of a century all those hundreds of heads of cattle, and sheep and horses belonging to the family would vanish like a morning mist.

They might have warned us that Englishmen would agree with Dutchmen to make it unlawful for black men to keep cows of their own. The gods could have prepared us gradually for shock, “ excerpt from Sol Plaatje’s Native Life in South Africa.

In later years, he withdrew from political organization and wrote the famous South African novel, Mhudi: An Epic of South African Life a Hundred Years ago. His pen was his weapon in the fight for restoring the dignity to the African people. He continued this battle until his death in 1932.

He certainly lived up to his middle name Thekiso – adding advantage or gain. We continue to reap benefit from his contributions to journalism and the African literary landscape.

First published in thejournalist.org on 5 July, 2014.

In collaboration with Mail and Guardian

![]()

Facebook: Mail & Guardian

Twitter: @mailandguardian

Instagram: @mailandguardian

LinkedIn: Mail & Guardian