Charlene Houston

Fawzia Lowe, who passed away at the beginning of September, was already in her 50s when she was thrust into the turbulent world of political activism following the arrest and imprisonment of her son.

It took all kinds of acts of bravery by people from all walks of life to topple apartheid.

Eighty-four-year-old Fawzia Lowe lived a fairly comfortable life in a decent neighbourhood, albeit zoned as a “coloured” area under apartheid’s Group Areas Act.

Her generation not only lived through the formalisation of racial segregation under apartheid but Fawzia remembered how the police had invaded the privacy of her family home to harass her parents who fell into two different race groups.

Fawzia’s generation had learnt that it was best to stay out of the spotlight and make the most of life without attracting the attention of the authorities. That changed the day her son was arrested and placed in solitary confinement.

During the 1980s the brutality of the apartheid government escalated, and large numbers of people were arrested, killed or went missing. The banned liberation movements in exile intensified their efforts while anti-apartheid campaigns in South Africa mobilised more people than ever before.

In June 1986 a National State of Emergency was declared which lasted for four years. Political gatherings and political activities were illegal and most organisations were banned. During this time all national and international media were banned from reporting on political unrest and government’s failing efforts to contain it. The State of Emergency gave the apartheid government sweeping powers to arrest, torture and murder people without any legal recourse. Although fear spread across South Africa, courageous activists remained determined to operate.

On 17 August 1987 amid increased state driven violence, heavily armed police and soldiers detained Fawzia’s son, Nazeem, in a pre-dawn raid. The next time she saw her son was when his captors brought him home hoping he would reveal an arms cache. Fortunately, Fawzia was a step ahead of them and they found nothing.

Nazeem was held under the notorious Section 29 of the Internal Security Act which allowed for indefinite detention in solitary confinement without access to lawyers, a doctor of choice (or any doctor in some cases) and family.

After much agitation by Fawzia, the police handed over a bag of Nazeem’s clothes to her. There was blood on the clothes indicating that he was being tortured in detention. This was the moment that Fawzia Lowe was infused with a transforming boldness and she became an activist.

After his arrest Fawzia resigned as manager of a fashion store to “run from one police station to the other” for information about her son. She stood out with her formal suit and matching accessories initially. As she became more radical, her dress style changed and almost always included a T-shirt with a political message and a beret (worn by many revolutionaries). In this picture, she is in discussion with Advocate Michael Donen. Like the other women, she educated herself about her new reality, as terms like remand, awaiting-trial prisoner, contempt of court and Geneva Convention became part of their vocabulary.

Fawzia and many other mothers met through organisations that supported detainees and their families. The women became a collective as they drew strength from one another and were commonly referred to as “the mothers.” There were sisters, brothers and fathers but mostly it was a group of mothers who could be seen protesting and later attending the various trials in court to lend moral support to each other. The mothers gradually became a force to be reckoned with, as they demanded the whereabouts of their loved ones, or that they be released.

The mothers paid special care to the needs of prisoners from outside Cape Town, since their families could not make the journey to visit regularly. Once solitary confinement was over and the detainees became awaiting trial prisoners, they were entitled to family visits. The mothers made sure that no prisoner went without a visitor. They knitted jerseys, brought fruit and took the dirty laundry home of those who had no relatives nearby. They saw nurturing and campaigning as part of one strategy. In the short term, the prisoners had to be provisioned but the long-term vision was to bring them home. Fawzia said, “We never accepted their imprisonment. We were angry and we had no weapons. So we used our tongues and our behaviour to anger the system.”

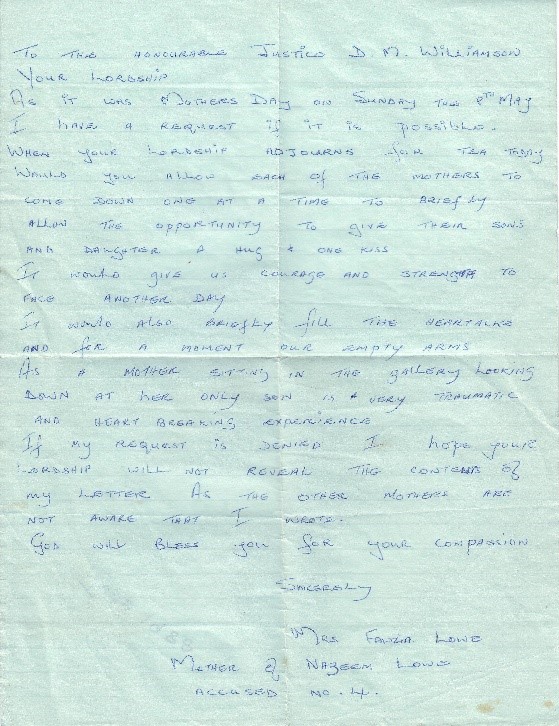

Fawzia could be quite playful and fun too. During her son’s trial, she secretly persuaded the Judge to allow the mothers to have physical contact with the 15 Forbes trialists during his tea break. She asked that they be able to hug and kiss the children since Mother’s Day (1988) had just passed. The Judge conceded much to everyone’s surprise!

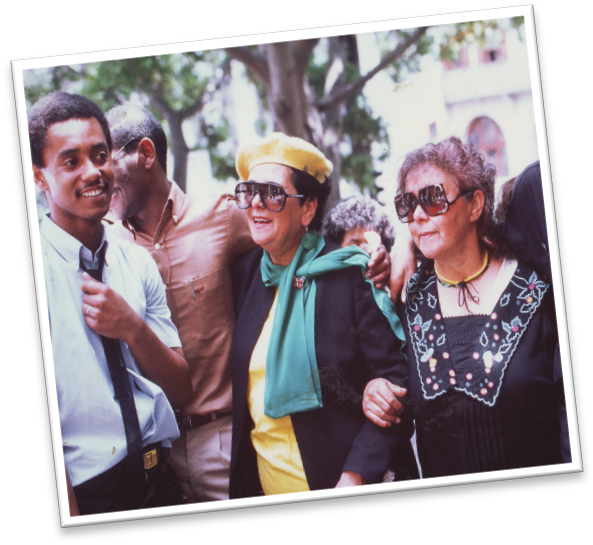

Activists would perform silent acts of protest such as wearing the colours of the banned ANC in separate clothing items. Fawzia’s activist outfits was a far cry from her glamorous fashionista image and made visible her radical transformation. Andrina Forbes, mother of Ashley Forbes, is also in this picture with Forbes trialists Walter Rhoode and Colin Petersen after they received suspended sentences.

After her son was convicted and imprisoned on Robben Island, Fawzia and other families of the Island’s prisoners who lived in Cape Town initiated activities that would keep attention on the Island’s prisoners. The police often set their dogs on them and they were also arrested from time to time. Fawzia was always at the forefront of these encounters. In this picture, she and another captive hold out a clenched fist salute after being arrested for demonstrating without permission.

During a night march in 1989 Fawzia bears a candle as a symbol of hope, notwithstanding the anxiety on her face as she looks across the bay to her son’s island prison. Alongside Fawzia a young man holds the flag of the banned African National Congress. ANC flags were seldom seen as those displaying them could be arrested. Fawzia was arrested five times in the four years from her son’s arrest to the day of his release from Robben Island.

In this image, UDF leader, Allan Boesak shares a laugh with Fawzia Lowe, June Esau and some other family of Robben Island prisoners, against the backdrop of an ANC flag. The women maintained regular contact with the leaders of the freedom struggle to keep the plight of prisoners high on the agenda.

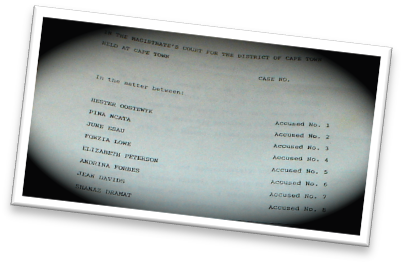

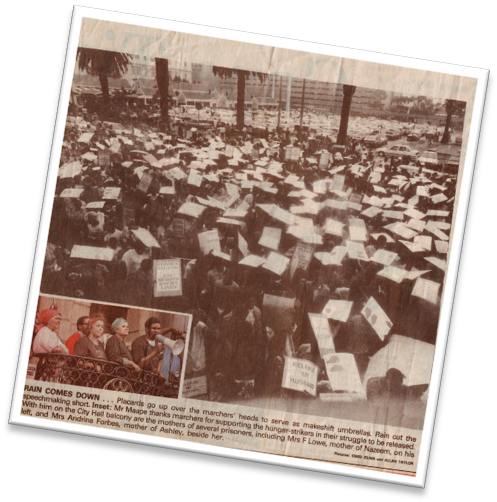

In February 1990 Nelson Mandela was released from prison, a signal that other releases would follow in keeping with President De Klerk’s extraordinary announcement that all political prisoners were to be released. But the mothers did not rest quietly – they turned the pressure up through their own release campaign. In February 1990 the Island prisoners embarked on a hunger strike demanding improved physical conditions and their immediate release. Eleven days into the hunger strike, Fawzia suggested that the women take advantage of the presence of large numbers of foreign media who had come to report on Mandela’s release. They also began a hunger strike and chained themselves to the gates of Parliament. Not only did their action receive international coverage, but many locals stopped to ask questions, giving them an opportunity to raise awareness. As a result Fawzia and seven other women were arrested and charged with attending an illegal gathering, for which they too were put on trial. They were Hester Oosterwyk, Pina Ncata, June Esau, Elizabeth Peterson, Andrina Forbes, Jean Davids and Shanaz Dramat. Just like Nazeem she was also Accused Number 4.

Small numbers of prisoners were released over the forthcoming year. Nazeem Lowe was released on 21 February 1991. This picture was taken at the press conference which was traditionally held as part of the reception activities for released prisoners. The receptions were a community affair and Fawzia would have had to muscle her way through the crowd to get close to her son. Hence her unusually dishevelled look. Next to the Lowes are Cecyl Esau who was also released that day and his friend Rabia Samuels.

Although Nazeem was free, Fawzia continued to campaign with the other women until the last political prisoners were released from Robben Island in May 1991. A strong bond continued between the women after the prisoners were released.

Fawzia Lowe dared to be an ambassador for political prisoners accused of terrorism at a time when the apartheid government had pulled out all the stops to crush resistance. The charming, glamorous lady from the southern suburbs became a feisty hero at the age of 52.

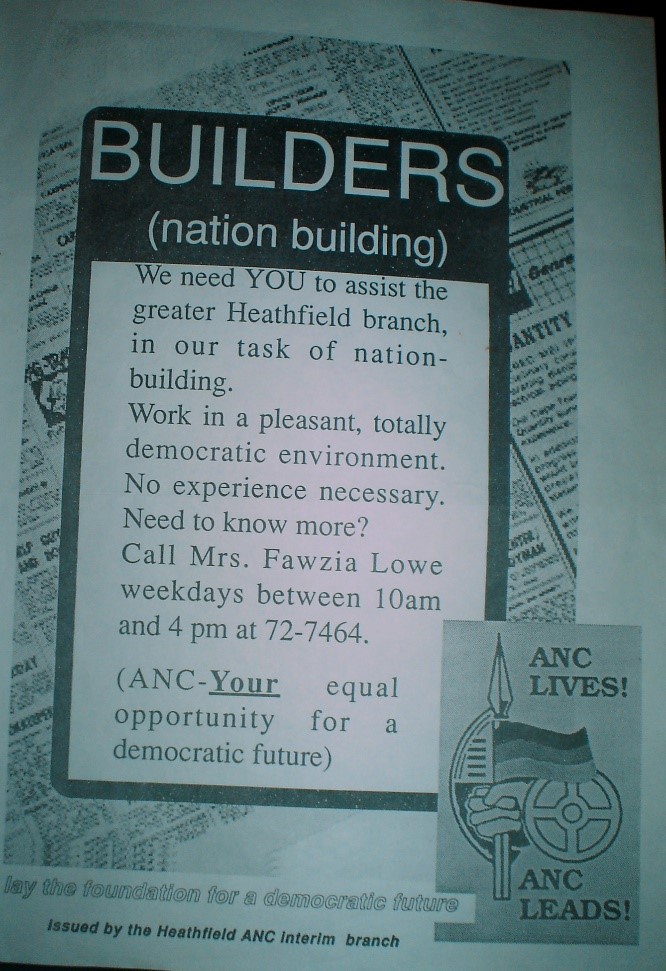

Fawzia also joined the LOGRA Women’s Group which became a branch of the ANC Women’s League after its unbanning. As part of a women’s rights campaign she and a few other women spread awareness as a rap group, performing in community venues around the Western Cape. She assisted in the establishment of the ANC branch in her local area after its unbanning and remained and passionate about the ANCs vision for South Africa until she passed on 1 September 2020.

I will always cherish Fawzia Lowe’s open mindedness, critical thinking, witty banter, her sense of humour and her brave and indomitable spirit. She is survived by her sons Nazeem and Adnaan and two of her daughters, Shanaaz and Scherene.