Victoria Britain

Basil Davidson, who died aged 95 in 2010, was a radical journalist in the great anti-imperial tradition, and became a distinguished historian of pre-colonial Africa. An energetic and charismatic figure, he joined that legendary band of British soldiers who fought with the partisans in Yugoslavia and in Italy. Years later, he was the first reporter to travel with the guerrillas fighting the Portuguese in Angola and Guinea-Bissau, and brought their struggle to the world’s attention.

For many years, he was at the centre of the campaigns for Africa’s liberation from colonialism and apartheid, endlessly addressing meetings and working on committees. Extremely tall and with a shock of white hair, and possessing the old-fashioned courtesy of the ex-army officer that he was – or even of the country gentleman that he eventually became after his move to the West Country – he was an unlikely figure at many of these often incoherent and sometimes sectarian events, usually run by student activists and exiles.

Among his friends were the historians Thomas Hodgkin, EP Thompson and Eric Hobsbawm. The Palestinian scholar Edward Said placed him in a select band of western artists and intellectuals with a sympathy and comprehension of foreign cultures that meant that they had “in effect, crossed to the other side”.

Born in Bristol, Davidson left school at 16, determined to become a writer, though he first made his living by pasting advertisements for bananas on shop windows in the north of England. Moving to London, he found his way into journalism, working for the Economist and then as the diplomatic correspondent of the Star, a now defunct London evening paper.

In the late 1930s, he travelled widely in Italy and in central Europe, and his familiarity with its geography and his capacity to learn its languages made him an obvious candidate, when the war broke out, for the Special Operations Executive – seeking to undermine the Nazi regime from within. His self-reliance, and lack of interest in received wisdom, soon marked him out. When sent out to Budapest, to stimulate the resistance forces in Hungary, he crossed swords with the British ambassador, who ordered him to stop storing plastic explosives in the embassy cellar.

In Cairo, he worked on plans to drop agents into Yugoslavia, first to the royalists and then, after much internal argument, to Tito’s communist guerrillas. Davidson was eventually parachuted into Yugoslavia himself, to join the communists in the uncompromising territory of the Vojvodina, the plain of the Danube valley across from Hungary. There, his exceptional physical strength and bravery were tested to the utmost.

When he returned to Yugoslavia at the end of the war, his companion on the visit, Kingsley Martin, editor of the New Statesman, recorded how “as we entered the villages, people would run out crying ‘Nicola, Nicola!’ (Davidson’s partisan name) and, after kissing him on the cheek, carry us both into their houses, where it was hard without offence to avoid getting drunk on Slivovitza.”

Davidson fought in Yugoslavia from August 1943 to November 1944, then transferred to the Ligurian hills of northern Italy. He and his partisan band seized Genoa before the arrival of American or British forces.

The war years marked him for ever. He fell in love with the comradeship, the trust and the spiritual force of endurance in the service of an ideal that he found with the guerrilla fighters. The lessons he learned about the muddle of war were important for his later work in Africa. In Angola and Guinea-Bissau in the early 1970s, and in Eritrea almost 20 years later, he found those same life forces and loved them. The subjective nature of his response to this history in the making, to deep friendships made and lost, made very painful the eventual unravelling of so much that he believed in.

The political lessons were less personally rewarding, since his willingness to collaborate with communists in battle would lead him in later life to be labelled by the Foreign Office as a dangerous “fellow traveller”. Davidson had never been attracted to Marxism, but his wartime experiences with Communist partisans coloured his general attitude towards the cold war struggle, first in Europe and later in Africa. If communists were prepared to fight against the Nazis, or later against South African apartheid and Portuguese colonialism, that caused him no problems.

At the end of the war, a lieutenant-colonel awarded the Military Cross and twice mentioned in dispatches, he turned again to journalism, working first for the Times as one of its correspondents in Paris and then as chief foreign leader writer in London. Out of tune at the Times, and especially unhappy with the western intervention that crushed the communist partisans in Greece, he left in 1949 to work for three years as the secretary of the Union of Democratic Control (UDC), the campaigning foreign affairs organisation set up by ED Morel during the first world war.

At the same time, he joined the staff of the New Statesman, where he was soon viewed as Martin’s heir apparent. It was not to be. At both the UDC and the New Statesman, he earned the undying hatred of Dorothy Woodman, Martin’s companion, and was accused of being a fellow traveller – “or worse”. Unable to return as a journalist to the Balkans, because of the cold war, he was taken by chance to Africa, and the continent soon caught his imagination, never to let go. Then, through an invitation from a group of South African trade unionists, he met Nelson Mandela, Oliver Tambo and other leaders of the African National Congress, about to launch its campaign of defiance against the apartheid laws of the Nationalist government.

Injustice, western hypocrisy and a whiff of revolution were enough to get him firmly engaged: later, from 1969 to 1985, he was a vice-president of the Anti-Apartheid Movement in Britain. He produced an important series about his African journey for the New Statesman, and then wrote a book about the crimes of apartheid. Soon he was listed as a “prohibited immigrant”, both in South Africa and in other parts of white-ruled Africa. That area of work was now closed for him.

So too was the New Statesman. On his return, Martin told him he was “proud to publish the articles, [but] if you have to hive off to another paper, I shall obviously understand”.

When he was offered a job as an editor at Unesco, the British government vetoed his appointment. Again, it was alleged that he was a fellow traveller, and that his articles were quoted consistently in Moscow. Doubtless they were, since they were very good, and Soviet reporters had even less access to Africa than those from the west. Far from being soft on communists, Davidson was accused during the treason trial of László Rajk in Hungary in 1949 of being an agent of the British secret service, as indeed he had been.

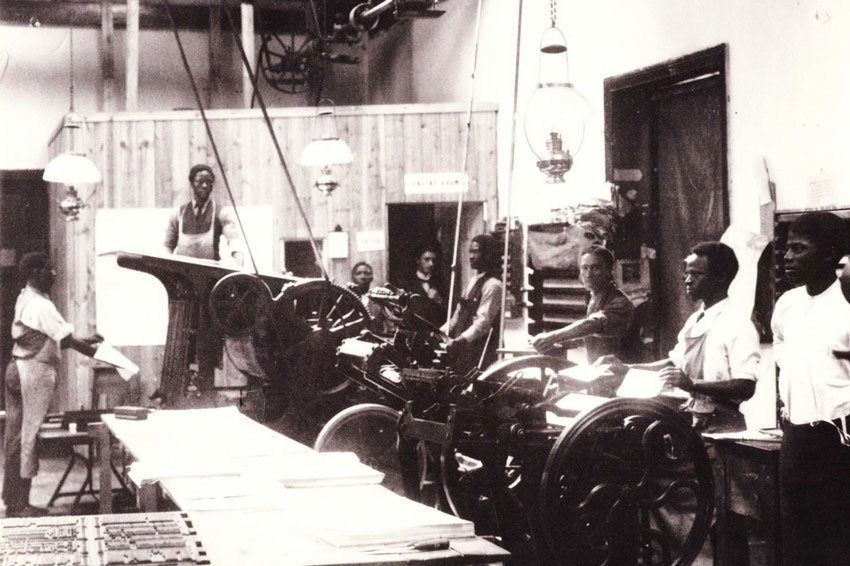

Davidson was rescued by the Daily Herald (1954-57) and then taken up by Hugh Cudlipp at the Daily Mirror (1959-62). Encouraged to take an interest in the Mirror’s publishing activities in Nigeria, Davidson made regular annual journeys through west, central and east Africa on the brink of independence from colonialism. Soon he was plunged deep into unwritten African history.

For a family man with three small sons, this was not an ideal profession. It was unfashionable, badly paid and meant long periods away from home. Davidson was no longer a journalist, yet nor was he a tenured academic. His wife, Marion Young, whom he had married during the war – she had also worked in SOE in Italy – somehow held their life together.

Books now began to pour out. The self-taught Davidson had an elegant prose style, at home with both fact and fiction. He wrote five novels and more than 30 other books. These were mainly about African history and included classic textbooks still in use in both east and west Africa. Davidson was enthused early on by the end of British colonialism and the prospects of pan-Africanism in the 1960s, and he wrote copiously and with warmth about newly independent Ghana and its leader, Kwame Nkrumah. He went to work for a year at the University of Accra in 1964.

Later he threw himself into the reporting of the African liberation wars in the Portuguese colonies, particularly in Angola, Mozambique, Cape Verde and Guinea-Bissau. Following in the steps of the great campaigning journalist Henry Nevinson, who had reported from Angola in 1905, he made an epic journey on foot half a century later that took him into the liberated areas of eastern Angola with the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola. The MPLA became the government at independence in 1975 and the epicentre of the cold war struggle in Africa.

Over the years the elaborate, CIA-run propaganda campaigns in favour of the MPLA’s main rival movement, Unita, led by Jonas Savimbi and aided by the secret invasions of the apartheid regime, frequently stumbled against Davidson’s authoritative counter-version. His scorn for the mainstream journalism that swallowed the western line on Angola was legendary. On Rhodesia, too, both the media and British government’s equivocation and connivance with South Africa’s support for the white regime found no more scathing critic than Davidson.

In the 1980s, with most of the African liberation wars now won – except for South Africa’s – Davidson turned much of his attention to more theoretical questions about the future of the nation state in Africa. He remained a passionate advocate of pan-Africanism. In 1988 he made a long and dangerous journey into Eritrea, writing a persuasive defence of the nationalists’ right to independence from Ethiopia, and an equally eloquent attack on the revolutionary leader Colonel Mengistu and the regime that had overthrown Haile Selassie. Davidson was invited to Havana to discuss the long-running Ethiopia-Eritrean war after the Cubans threw their weight behind Africa’s latest revolution. He was irritated by the personal enthusiasm of Fidel Castro for Mengistu, and by the large numbers of Cuban troops sent to help him in his border war against Somalia – although they did not fight in Eritrea. Davidson expressed no surprise at Cuba taking on a new African protege, but he retained his own unfavourable view of Mengistu.

The eventual turn towards repressive government taken by his friends in the Eritrean leadership, when other leaders to whom he had been close were imprisoned in Asmara, was a sad rerun of a similar political trajectory he had witnessed in post-independence Angola. He did not like talking over these matters, but he did not disguise his disappointment. Critics from the right were swift to condemn the early judgments that he had made about these revolutions that had turned sour, and even some of his friends would have welcomed more debate.

In 1984, Davidson embarked on a new career in television, making Africa, an eight-part history series for Channel 4. He was excellent on screen, bringing to an unexpectedly wide audience a vision of Africa far from the usual famine-and-corruption cliches that annoyed him so much. His alternate version of African reality reached further and deeper than he had imagined possible, though he continued to write, producing notably The Black Man’s Burden: Africa and the Curse of the Nation-State (1992); the collection of essays The Search for Africa (1994); and his final book, West Africa Before the Colonial Era: A History to 1850 (1998).

He received honorary degrees and appointments from many universities, including Edinburgh, Birmingham, Bristol, Manchester, Turin, Ghana and California, and was also decorated by Portugal and Cape Verde for his services to their history. Apart from his military medals, the British state was studiously uninterested in recognising his talents and his service.

He relished the irony of being decorated with great warmth in 2002 by the prime minister of Portugal – once an activist against the fascist regime that Davidson had done so much to bring down. And when the Cape Verde government chose to decorate him in 2003 in an Angolan embassy where the ambassador was a former prominent official of his old opponent Unita, he remarked drily on the surprising reconciliations demanded of those who live long enough.

Basil Risbridger Davidson, historian and campaigner, born 9 November 1914; died 9 July 2010

(This article first appeared in the Guardian)