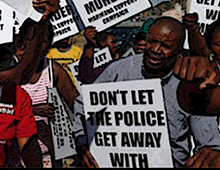

Neil Cole

Citizens should not be duped into believing that winning a trophy will transform our country or build social cohesion.

The bok team that won the 2019 Rugby World Cup was a decidedly different team to the one that lifted the trophy in 1995, and also in 2007. The 2019 team has a black captain and the tries by two black players won the final for South Africa. This was a moment that the country was yearning for after a week of depressing economic data – unemployment at 29%, public debt going above 60% of GDP, and all of this amidst a country that is measured as the most unequal in the world.

The miracle that was desired was not for the boks to win, as that was a given. The desired miracle was that the win would unite the nation and provide the inspiration, the invincibility, to overcome. But moments like these seldom, if ever, achieve their desired outcome. Moments like these don’t transform societies and have a minuscule effect in building social cohesion. The two things missing from our country.

I remember the jubilation of my mainly white colleagues when the boks beat Australia in the opening match of the 1995 Rugby World Cup, and I remember the moment when Mandela walked onto the field to join the bok team that had beaten the All Blacks in the final of the same competition. But I also recall my unease. South Africa was one year into its democracy, following many decades of brutal apartheid rule by the National Party. The privileges that apartheid had bestowed on white South Africans were largely untouched, except for the abolition of segregation laws and a government of national unity in the Union Buildings.

Education was stubbornly segregated and unequal, the majority of black South Africans still only had access to under-resourced and under-staffed health care facilities and many categories of jobs were still the tacit preserve of white South Africans. The bok team with its one black player and its entire rugby administration had not even sniffed at transformation.

Leaping forward 24 years, the way that the Eben Etzebeth racism scandal is being dealt with, and despite a very different looking bok side, it’s clear that social cohesion and transformation pervade us as a nation. A laager-like mentality has been thrown around Etzebeth, despite serious allegations of hate speech and assault. For the desire of a world cup trophy and desperation for opium-like euphoria to distract a nation from depressing socio-economic statistics, a person that is alleged to be an ardent racist is given the benefit of ‘innocent until proven guilty’. He was allowed to represent the country in the colours of our national rugby team. Many are prepared to overlook the scandal, but very many are also not. This stubborn ‘hotnot’ refuses to stick his head in the sand. Not only does the Etzebeth scandal reveal the under-belly of a deeply divided society, it is also clear that we are not yet ready or convinced that the ‘victim must be believed’, especially in cases of sexual and racial violence. It could also be that the victims in this case are taken less seriously because of their apartheid-era minority status as coloureds and ‘hotnots’. All the symptoms of a failure to transform and a failure to build social cohesion.

Mandela’s infectious laughter as he shook the bok captain’s hand in the final of the 1995 competition artificially melted away our reality into one of those opium-like, ‘rainbow nation’ moments. But that moment has passed and we should keep it in the past. Selling the euphoria of a sporting victory as an ingredient for social cohesion and transformation is farcical. Twenty-four years after the Mandela moment we should know that it is devoid of the ingredients required for a society to transform and build social cohesion. The fact that we were duped is not the fault of Mandela, but our own. And the signs are there in the celebrations of the current victory that seem to indicate that South Africans from across the socio-economic divide are ready to be duped again.

Miracles are miracles – meaning that they are not real.

Moving into the Mbeki era, the picture of what transformation meant became clearer. Several very tangible steps were taken, but thwarted by gaps in governance and capability, but nonetheless good intentioned. However slowly, the public sector was transforming, not so much the private sector, and more black players were entering the bok team. The Mbeki years also revealed the reality of transformation, that there was going to be no miracle, no matter how much spirituality the Arch was covering us with. Transformation in South Africa was going to need a capable state, very significant investments in social protection, education, health, and all the other things that grow an economy and restores dignity. Mbeki removed the opium-like euphoria of the Mandela years, and started to reveal that Mandela’s embrace was not a start to transforming South Africa, but neither was it trivial. Transformation was going to involve hard work, and not driven by miracles or ‘one-nation’ nonsense that is associated with a game of sports. I remember Mbeki looking slightly uncomfortable in the presence of the jubilating bok team that won the Rugby World Cup in France in 2007. Maybe sport is not Mbeki’s thing, and I suspect that he was not fooled by the contribution of euphoric moments to transformation and social cohesion.

Our next chapter in transformation or better described as (un)transformation starts with the glee on the faces of the supporters of Zuma and the soon to be launched capture of the state project. What follows is nine years of the weakening of the state’s capability to transform society, despite the aptly titled ‘radical economic transformation’. The less one knows about transformation, the more likely that ‘radical’ will be used in the title. Not only did Zuma further weaken the state’s capability to implement a coherent transformation plan, it also hardened the belief amongst certain groups that black people may not be capable of governing, as evident in the swing to the right in the 2016 local government elections and the even greater shift to the Freedom Front Plus in the 2019 elections.

The crimes that Etzebeth are alleged to have committed, and the laager that ensured his continuation in the victorious bok side, is in many ways the result of a transformation failure, coupled with a hardening of rightwing, racist attitudes in South Africa. It is alleged that Etzebeth and his wolfpack went on the prowl on that fateful night. Their victims were a group that apartheid legislation classified as coloured and casually called by the derogatory term ‘hotnots’.

Reading the account of Etzebeth’s alleged victims, it reminded me of a story of Van Riebeeck going on recreational hunting adventures of the indigenous people – his hottentots (hotnots).

The Etzebeth scandal and how it has divided a nation, mainly along racial lines, reveals the miniscule effect that Mandela’s embrace had in transforming the country. It also provides a lesson to those who take an interest in how societies transform and how social cohesion is built. My advice is to stay away from magical and farcical moments. A transformed society needs to provide: quality education and health care for all, an opportunity to find or create a decent job, safety in your home, place of recreation and workplace and racial and gender equality. Social cohesion is built in parallel with real change. Citizens should not be duped into believing that winning a trophy will transform our country or build social cohesion.

The expected miracle of the 2019 RWC victory will fade, and the reality of its minuscule effect will soon be felt. And when it fades, we will be left with a member of the winning bok team defending very serious charges in the Equality Court. We will also be left with our grim economic outlook. Sticking our heads in the sand on both of these will find ourselves searching for the miracle in France at the 2023 Rugby World Cup.

Photos: Twitter/@HumbeTheDreamer